Since the birth of healthcare as an institutionalized system, development of medical treatment often came with a cost of patients’ health and wellbeing. A national report “To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System” (1999, US) embarked on iatrogenesis: the problem of patients’ death and injury resulting from medical errors.

The interest in increasing treatment’s efficiency and patients’ safety, laid grounds for new medical education schemes. Among them, simulation is now becoming a standardized practical learning model in healthcare.

Simulation relies on re-enactment of plausible events in a real-like, simulated clinical environment, including the patients’ bodies who are replaced with manikins and simulators. It therefore allows avoiding the presence, and consequently potential harm of the patients during the training. The more realistic the simulation and involved in it artificial bodies are, the more immersive the training and effective its outcomes.

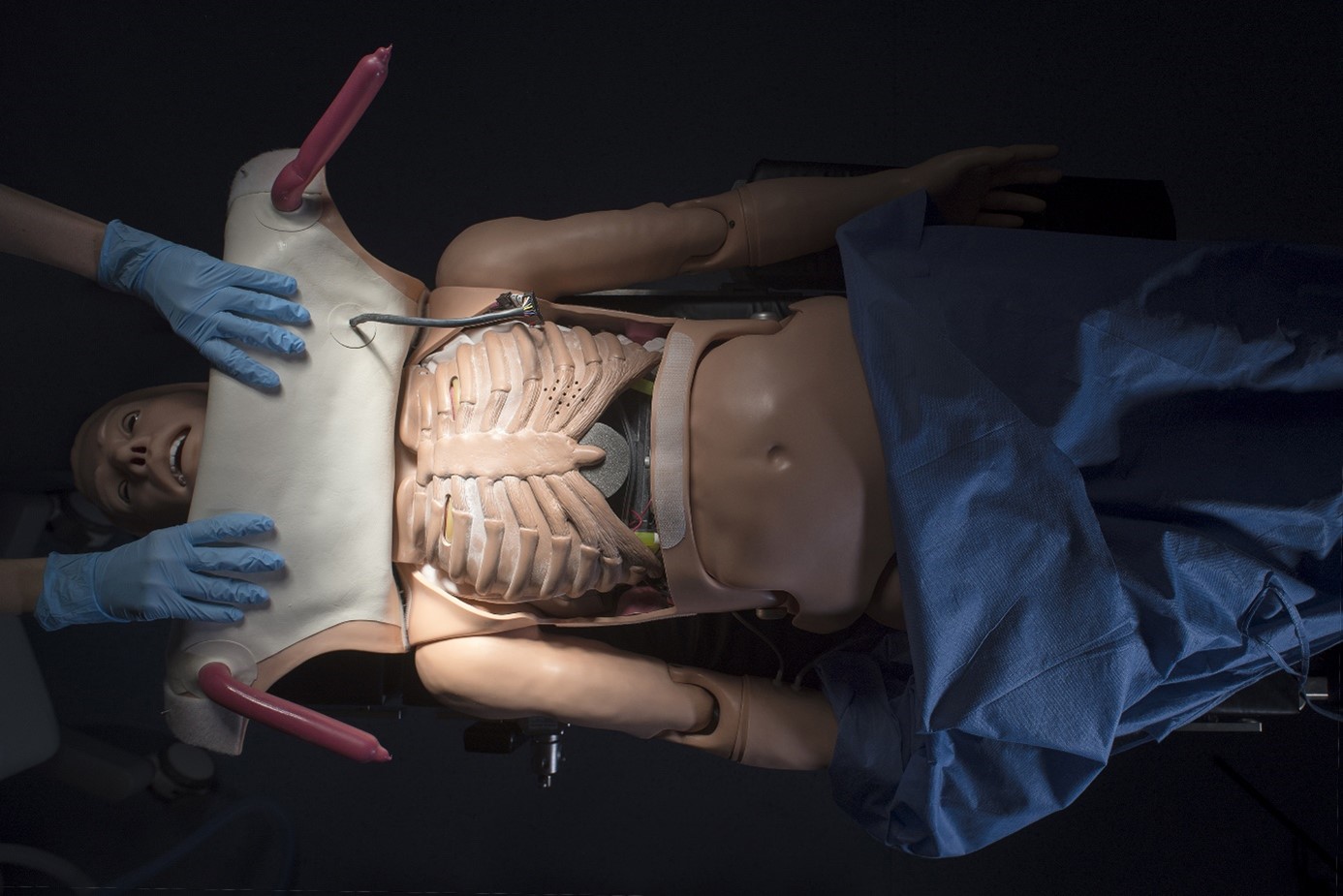

For the needs of Medical simulation, infrastructures and objects are being manufactured. The centerpiece of medical simulation is the patient: thus the quest of the simulators’ industry is to produce the most realistic replica of the human body. Gaumard (USA), Laerdal (Norway), CAE (Canada-USA), NASCO (USA), Kyoto Kagaku (Japan), Sakamoto Model (Japan), SimBodies (UK), are among the brands specializing in manufacturing the medical lifelike models of the human bodies. The proxy-bodies of male and female, adults, adolescents and infants, represent different levels of realism and technological advancement. It is difficult to escape an association with sci-fiction when looking at the life-size figures whose silicone bodies are under layered with steerable mechanisms which make the human ersatz move, react, breathe, bleed or talk.

The simulators, although designed for utilitarian purposes, like anatomical drawings and models, can be seen not simply as learning aids, but as “artefacts of the human, cultural meaning-making activity called ‘science’.”(Ebenstein, 2020) Regarded as such, the simulation manikins and props emerge as products of culture and history, reflecting the contemporary world views on human body, and on what, whose bodies are recognized as “medical”.

The production of medical simulators in the past was often linked to socio-cultural taboos, such as restrictions towards exposing the female body. For that reason, the obstetric mannikin was among the first simulators to be developed. The early birthing mannikins, such as “La Machine” constructed by Angélique Marguerite Le Boursier du Coudray (1712-1794), a French midwife connected to Louis XV’s court, represented a pregnant abdomen with uterus. The prop was easy to transport so that the training lessons could be provided to midwives in different places across the country.

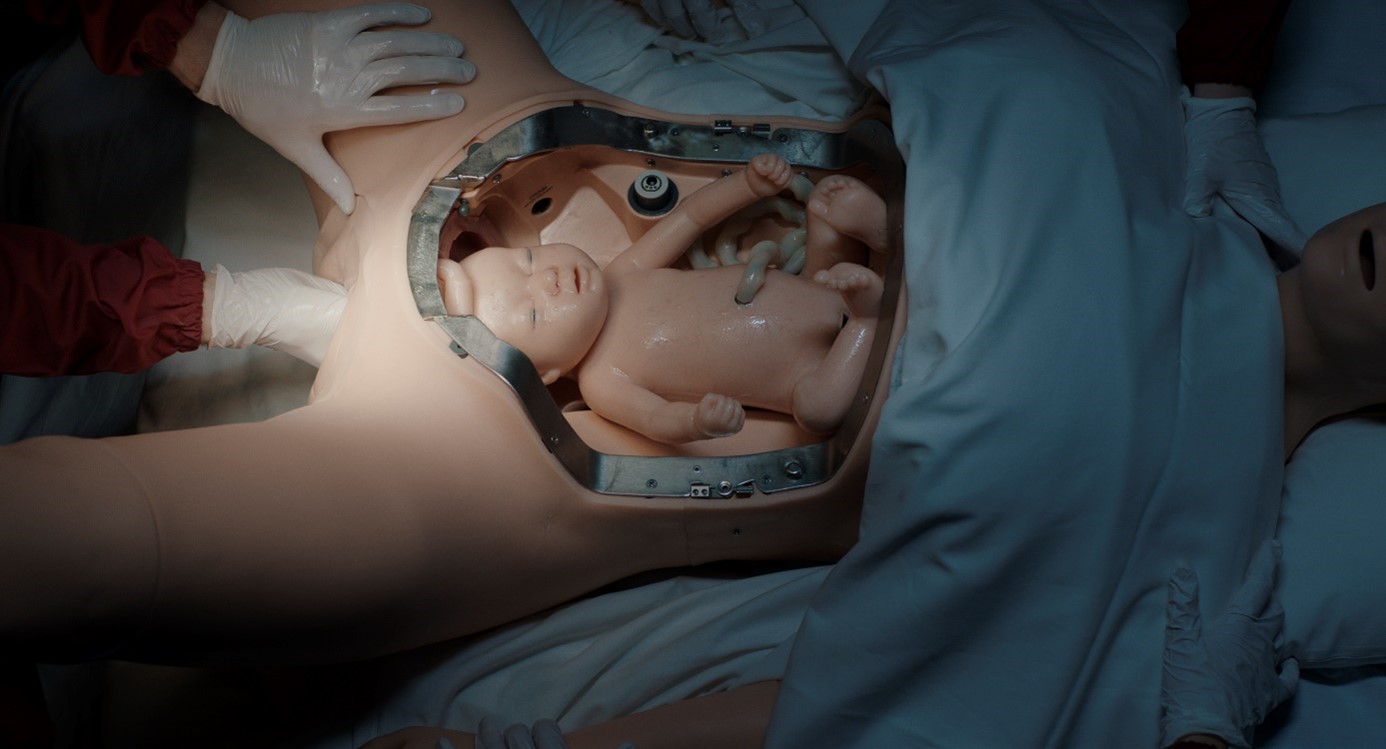

Through the 19th Century, birthing machines would evolve into capable of leaking amniotic fluid and blood artefacts, manufactured across Italy, France, Germany and England. In the fin de siècle and early 20th Century, the models evolved into full-sized, posable female figures. In the 21st Century, the automated life-size birthing mannikins, along with realistic newborn dummies, are frequent centerpieces in medical simulation centers worldwide.

Evolving birthing mannikins witnessed the socio-cultural changes around childbirth, beginning from the woman-made "La Machine": an artefact pertaining to the women-only praxis performed by female midwives in domestic spaces in 18th Century. The increased production of obstetric models in the following 19th Century was propelled by male-midwives. The process of appropriating the so far woman-only praxis by male doctors came with new, intervention-based delivery strategies which included use of tools (forceps). The movement promulgated labor as a matter of medical, scientific expertise – as opposed to the traditional midwifery, which it stigmatized and rendered as obsolete, unprofessional.

Increased rendering of pregnancy and childbirth as necessarily risky conditions, augmented the presence of medical care around childbirth which over 81% is estimated to now happen in medical facilities (Day, 2020), while the home-birth is widely seen as potentially dangerous. The prevalent presence of clinical care and medical procedures around the parturient bodies in the 20th and 21st Century have been recognized as medicalization of pregnancy.

Thus the emergence and evolution of the female-automated body was more than a utilitarian solution, but a symptomatic artefact of the times. The contemporary birthing mannikins, firmly installed in the clinical simulated environment, draw out the contemporary recognition of pregnancy as a “medical condition”.

Obstetric simulation draws out another question. When observing a birthing simulation in the present, the prevalent women's presence is noticeable around the laboring mannikin. This draws out the existing inter-changing gender imbalance within ob/gyn practitioners, which now re-emerges as the so-far predominantly male staff is now being replaced by women (example: gender ratio within ob/gyn practitioners in US: male: 15%, female: 85%).

Medical simulation training centers encompass the complexities and ambiguities of contemporary healthcare, in which childbirth and pregnancy are engaged in. The intention for ameliorating the medical care’s standards, medical performance and promoting patient-centered approach blends with modelling the healthcare institutions as a “controlled” and “corporatized” environment.

The automated figure of a parturient woman mechanically giving birth in the medical surroundings can be seen as a question mark regarding the progressing medicalization of pregnancy, agency of parturient women within the healthcare system and the gender-imbalance within the obstetric professionals.

Photography & text: Agata Wieczorek