From heirlooms to healing by Chloe Sastry ARSP

Working with her family’s uneven archive, the photographer confronts and reconstructs difficult stories and finally finds a sense of “home”.

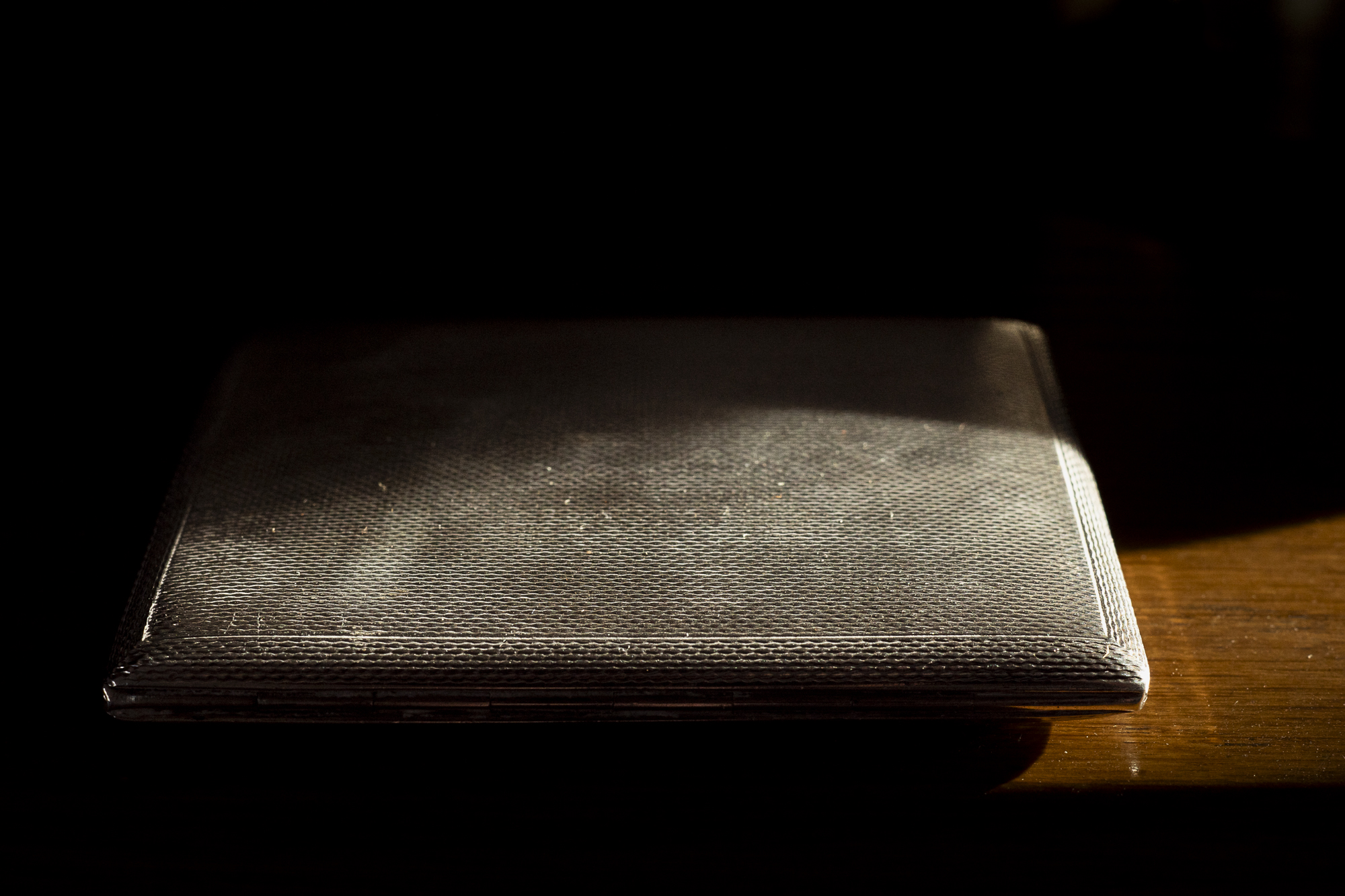

I have always felt a conflict between the historical items in the family archive now in my stewardship and my own subjective recollections. From my father’s side: dusty boxes of revered photographs, ephemera and objects I felt obliged to store away —- Hermès scarves, engraved silver, inherited jewellery and collectable china —- all an extension of my paternal family’s self-esteem. From my mother’s side, just four photographs remain, their erasure in plain sight.

This carefully curated collection only told half the story. It put me in mind of the wider postmemory work of academic Marianne Hirsch, who describes how domestic photography is "the family's primary instrument of self-knowledge and representation."

Over time I’ve been able to reframe this obsession with signalling social hierarchy through the indexical recording of heirlooms. The true value of an archive lies somewhere beyond its material worth. Perhaps the obsessive collecting, recording and passing down of objects was my father’s family’s way of connecting, of saying: “I love you and I trust you with this thing that is part of me.”

Despite their differences, both sides of my family were just trying to show me love in their own ways. I wanted to find a way to honour that, while also acknowledging the parts of my history that were missing or forgotten. And so Past, Imperfect, my collaboration with the family archive, was born.

"When I die, this will come to you"

‘Reconstructing’ memories

I am always interested in what people are not photographing and how I might tangibly represent the absence I feel. I responded to the dominant archive by

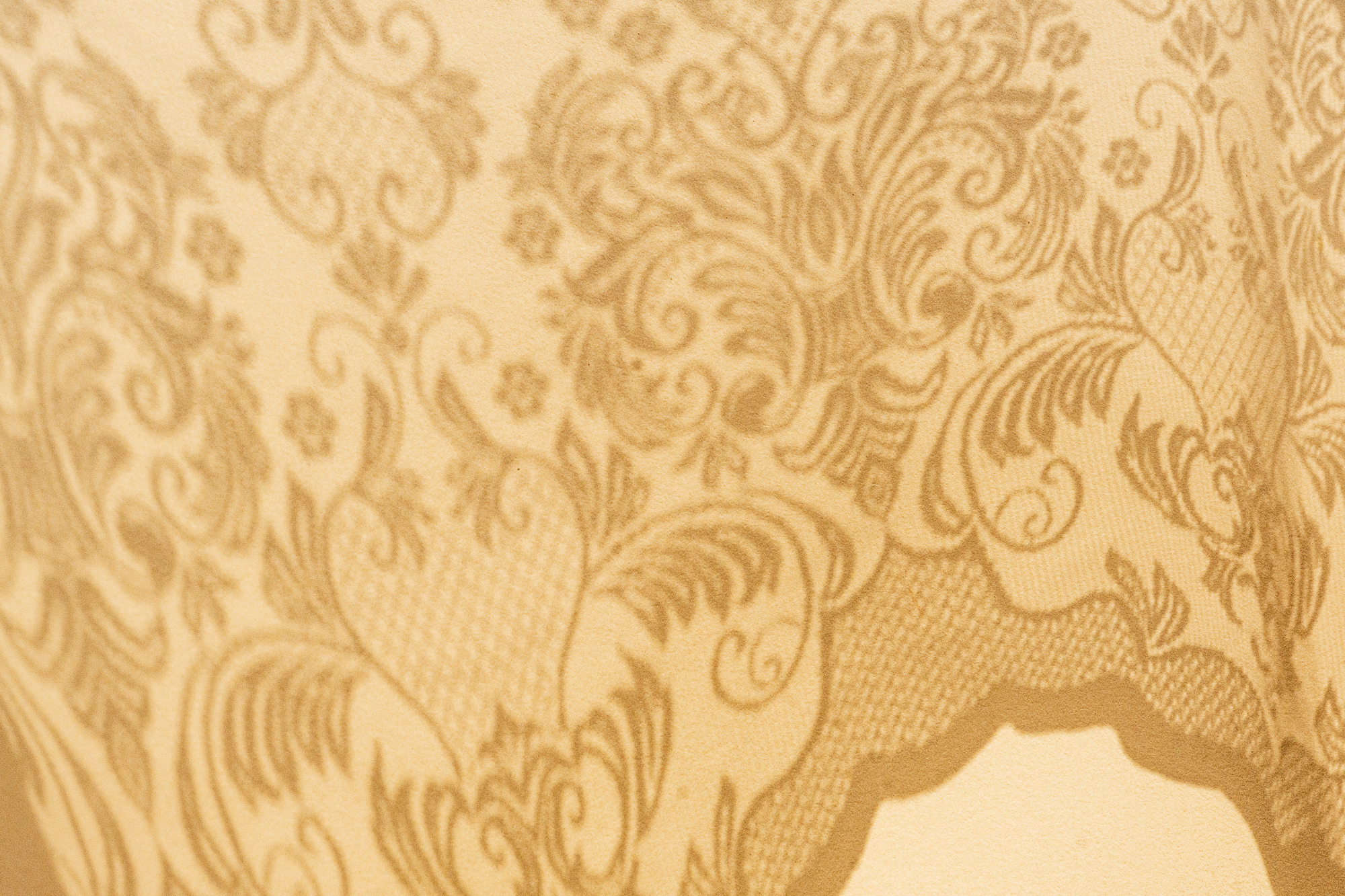

exposing the material traces of people and time on these treasured objects — inserting the suggestion of my anger and frustration — while simultaneously making visible the forgotten part of my family archive. I hope to create a legacy of images connoting value to the material realities of my maternal grandparents’ home.

By sourcing and photographing the more undistinguished missing objects, fabrics, and foods, I welcome viewers before taking them deeper, beyond the assumed insignificance of acquiring “things”. I removed these objects from their traditional domestic settings and staged them in new ways, hoping to reanimate them and uncover the personal and social narratives they hold. This controlled “reconstructing” of my memories has limitations but is no more a deception than the selective compositions and recording of my identity by the original family archivist. I see the irony in my using inherently fallible photography to contest the archive.

Rephotography allows me to show every remembered detail from my maternal grandparents’ home, a forbidden, cosy haven of games and comfort food. Responding to the original photographs, yet cutting out sections, mirrors the removal that happened and allows me to preserve anonymity.

"My family never got a look-in, you know"

Flawed communication

Within the project, I introduce sections with my childhood memories of blunt, restrained phrases uttered by both sides of the family — all flawed attempts at expressing the same concern. I prefer to keep who said what ambiguous, to convey the emotional charge of the dissonant communications of love from each side that continues to haunt me. I pair each caption with a small, tea-toned cyanotype fragment from each home, slowly formed, sealing it into its vaguely remembered world.

It was a challenge to blend the diverse image types and still retain a coherent whole. That said, the inherently fractured nature of the family and of memories themselves perhaps mirrors the naturally disjointed construction of amateur albums. Moving between warm light and formal dark backgrounds reflects my original, naïve push and pull between the warmth of “good” and the detached formality of the “bad”.

"The true value of an archive lies somewhere beyond its material worth"

A new heirloom

Past, Imperfect has become an intimate, hand-stitched album — a tactile object in itself — which I in turn can pass down. Sharing the work to date has shown me people are interested in talking about the family archive and has had the unexpected effect of evoking nostalgia, creating a space for some to share their own difficult family stories. I am now exploring relevant networks for a wider, more socially engaged practice. This is a complex area, and I am therefore joining Dr Neil Gibson’s certificated Therapeutic Photography course in September 2025 to more rigorously explore the potential to integrate photography for self-expression into my professional mental health and social sector work.

The project will evolve as I continue to explore my archive. Creating this counterhistory allows me to untangle the ties of others and find my sense of “home” inside myself. I am acknowledging my loss and recognising the role of significant objects in understanding my longed-for sense of identity and belonging to both sides of a family divided by class but united by a common desire for meaningful, loving relationships. My erstwhile urge to discard material heirlooms is shifting now that I appreciate their role beyond their physical form. An absence of evidence is not necessarily evidence of an absence.

I cannot change an imperfect past, but I hope to create a new, more fluid legacy for my children.

"Gosh there wasn't anything really wroth passing down"

All images © Chloe Sastry

About Chloe Sastry ARPS

Chloe Sastry is a photographer based in London, UK. She has recently gained an MA in Photography from Falmouth University. Through her previous career in the social sector, focusing on mental health and horticulture therapy, she developed her lifelong interest in the universal human experience and what motivates us all. Sastry is particularly interested in how photography allows us to express our most difficult feelings and, in turn, relate more authentically to others. Her current projects explore self-expression within the themes of family origin, loss and memorialisation.

Instagram: @chloesastry

Website: www.chloesastry.com