Eye Mama: Poetic Truths of Home and Motherhood

Karni Arieli in conversation with WE ARE Magazine’s Poppy French

I had the opportunity to speak to Karni Arieli when she was in the thick of it with the printing and promotion of her long-awaited book, Eye Mama: Poetic Truths of Home and Motherhood; the arresting 200 image book which accompanies Karni’s long-term project, social movement and open collective virtual space started during lockdown, Eye Mama. Karni spoke to me from the Bristol studio she shares with her partner Saul Freed, with whom she also directs commercials, musical videos and short films.

Karni was warm and extremely passionate about the “mama gaze” and her project.

We got into talking straight away, and as two mamas with small children, we of course, started off discussing the childcare juggle, community, birthing in a pandemic and how it is not possible for us to discuss photography without discussing motherhood.

One Day-old Misia and Me © Jadwiga Bronte

We’re supposed to be talking about photography, and we’re deep into talking about motherhood.

Well, there is always an intro like this whenever I talk to anyone about Eye Mama because this is life in Eye Mama.

I'm in a situation with my son who, obviously I love very dearly, but he's in that stage where he’s not into me. It’s all about Daddy and his grandmother. I feel like I'm just not quite doing anything properly; not finishing anything, giving that enough of my time. I probably was like that before I had a baby as well, but now it's bigger, louder, more prominent.

Absolutely. My kids are saying, “When's Eye Mama gonna be over”? The ridiculous thing is that the project on motherhood is taking me away from motherhood. The juggle that I've had to do for Eye Mama: I’ve never founded a project; I've never been a curator; I’ve never done a community outsourcing project. I didn't know what it entailed. I think if I knew I would never have gone on this journey. Now that I know, I have no return. Just like with a kid, I've given birth and I have to see it through, How do I juggle kids who still need me, my own space and time, my day job, as Eye Mama doesn’t pay? And yet I've done this project that now has thousands of followers and turned it into a book, and I have to promote it with little resources. I often feel like I'm failing at everything. But sometimes I feel like I'm succeeding a bit at something. That's enough to push me through most of the time. In the end, what would I give up? Not have kids? Not working at home with my partner on my film? Not make Eye Mama? No. So there's going to be a compromise.

When you look at anyone who does anything that's meaningful, or time consuming, they say they wake up at 4am and do their work before the kids are up or work until midnight. There's no way around it, you're going to be overworked. You're going to always be compromising because I think child rearing was originally not meant to coexist with working.

Untitled © Noa Maccabi

It’s so refreshing to hear you talk about the truth behind creating the Eye Mama book. It feels to me like the whole project from fruition has been about sharing the truth and honesty about motherhood and child rearing.

Eye Mama is about sharing truth and beauty, not just the sick but also the hugs and the connection; all the stories that are personal. Each story is very different because it comes from a particular photographer; from a particular mother. I think sharing your own story is a superpower. Women often don't realise that sharing their own story and being in control of it, in a way, is so empowering to yourself as an artist and as a mother.

Let’s move on to discussing the landscape of photobooks about motherhood and the huge gap in the market that there seemed to be before the pandemic.

Eye Mama is a professional portfolio by photographers who happen to be looking at the topic of motherhood. That’s never been done before, at least not at this scale. There is no other portfolio looking into the home and motherhood by mothers who are artists. There is Home Truths (Photography, Motherhood and Identity edited by Susan Bright) which is a great book, but only features very established artists. I was wondering how come that never got taken further?

What's different about Eye Mama is that it's democratic and inclusive. Anyone who considers themselves a photographer and / or a mama can submit images. They don't have to prove they've been published. They don't have to show that they've had an exhibition. They don't have to be of the calibre of certain artists. They just need to be an artist and a photographer of some professional format. Also the genres mix, there's not many platforms that have photojournalists, art photographers, portrait photographers, and very established and unknown artists in the same place.

Father and Son © Leah Devun

I’m trying to level the playing field. We’re not going to do what all the male gaze platforms have done historically, or even just the very high art curation platforms where, if you haven't had two books and two exhibitions, you don't exist. Part of the motherhood penalty is that you couldn't exist because you weren't able to attend and show yourself and be there and push and shout, because you are caring, and since that caring doesn't matter to anyone, it's behind closed doors. You've never been acknowledged for that either.

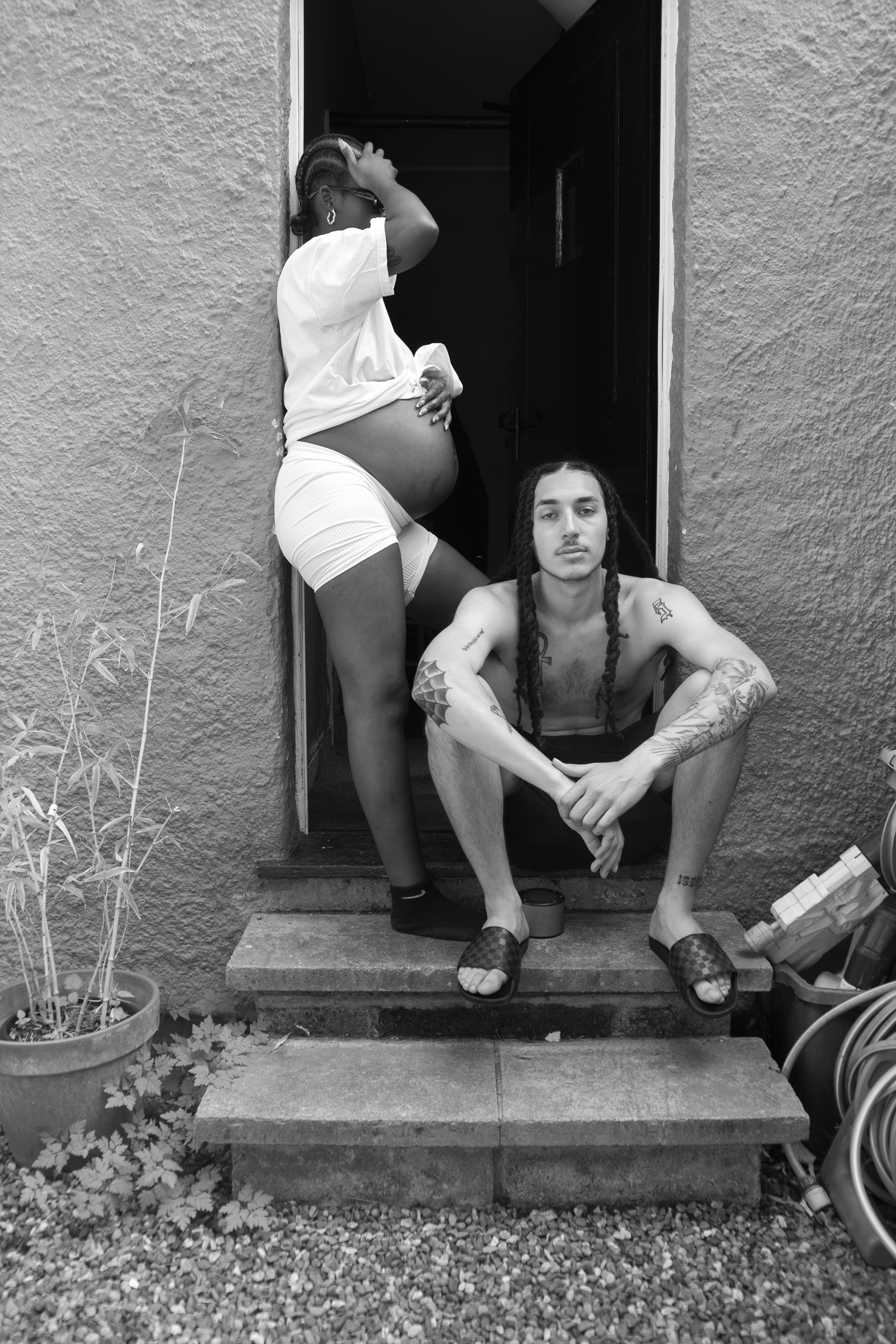

Mother and Daughter © Asia Werbel

Some curators were against me working with women who were less well known. It would have been easy to just pick up the well known women and put them on my platform, but that's not going to be making change. What I wanted to do is pluck women out of obscurity and out of the unknown, who have submitted to me, and actually it's more exciting to me to find those women, because that's where the real curation is. I feel like if you are going to make a platform for women these days, you should flip everything on its head.

Absolutely, you’ve been a real explorer in that sense. Did you find Instagram to be a useful tool in building the community, with photographers using the Eye Mama hashtag to get their work discovered. Was it key for setting up the platform?

When it came to setting up the Instagram page I was petrified and I delayed it as long as possible. I ran it by Alessia Glaviano (Head of Global PhotoVogue) and she said that it sounded cool. She thought it had something in it and encouraged me. I couldn’t avoid it in the end, I had to set up the Instagram account because I only knew ten women who I could reach out to. That's not going to be a project. So I put ten women up on the Instagram, asked them if I could repost, tag them, and then set up the hashtag. Two years later, we've got 50,000 submissions, 17,000 followers from 50 countries and 4,000 images were submitted to the open call from 1,000 women. It grew very fast and it's been a blessing and a curse.The strength of social media and Instagram has been the community and the word of mouth. Women in the middle of the night write to me "I'm really struggling with breastfeeding and here’s an image". I became therapist, social worker, friend, curator and photographer to all these women who were suddenly my sisters in a community of women who are both mothers and artists. They became my psychic family, as Gloria Steinem calls it, the group that you select that you can connect to. I was collecting more and more of them, and they were so grateful, especially in the pandemic, to be showcased. They were giving me a lot of feedback and reassurance that they really needed the platform, that there was a place for their images that hadn’t previously existed.

At first, when you have ten followers, nobody wants to be part of your platform. Then you have to reach out to people. Through them, the energy slowly built the momentum. Then you get an article, in the British Journal of Photography, in Vogue, Creative Review and The National Geographic, which was the big one. Then you get a lot more women coming to you (which includes non-binary, trans women, anyone who identifies as a woman).

Mum and Dad © Jade Carr-Daley

Self-portrait with Harris and Lewis (147 days) © Arpita Shah

That’s really interesting that you’d created a space where everyone felt they could come to you with their images; their story.

It didn't come to me immediately, but with IVF, child loss, abortion, miscarriage, adoption, fostering, all of these things had to be part of the Eye Mama narrative. That's why I didn't call the project motherhood, because I feel motherhood is very much related to the historical take on motherhood - the male portrayal of what motherhood is and what society's concept of a mother is. So I detached from that by using the word “Mama”. And the word “Eye” is crucial. I and eye, what your identity is, what your eye is. In the sense of narratives, we really wanted to keep it wide open and said “send us your struggles”. Being a mama is also the struggle to be a mama or not be a mama.

Our focus is on all different types of family; single mums, same sex couples, and anyone who identifies as a carer who lives with children rather than only people who are giving birth. Separating that element out of it has been crucial. The weird thing is that I had to give myself permission to grow and change the rules all the time because we started off in one place, but when you've learned things for a year and looked at images for a year, I was being educated by my own platform. After making the platform, I felt much more connected to someone for example in Indonesia, because I chatted to them in the DMs (direct messaging on Instagram). Once they send you images, you feel like you know them. I'm a middle class, white Jewish mum in the UK. I'm half Israeli so I'm a foreigner in the UK. I don't feel quite British but I don't feel completely detached. This platform has helped me empathise and connect a hell of a lot more than I did previously, also with the struggles of motherhood, which I didn't have personally and you don't always connect to those stories if you don't see them. So, I suddenly get sent hundreds of these images, whether it's cancer, IVF, child loss, abortion, marriage breakup. In some ways, it's a lot to take on, I have all these visuals, and I would sometimes break down because it'd be too much. But then there's the balance of it, there's a lot of amazing things that you see; a lot of power and strength.

Divided Body © Shindy Lestari

Having all these images, it must have felt almost impossible to curate them to the limitations of a book format. How exactly did you go about it and how did you make the decisions on what needed to be represented?

It was clear we needed to represent everything. But of course, when you sit down with 4,000 images, and you have to get to 200, you have to ask what you’re going to lose. We created a jury: Ana Casas Broda; Aldeide Delgado; Alessia Glaviano; Charlotte Yonga; Elinor Carucci; Kana Tanaka; Sarah Leen; Smita Sharma; and Ying Ang - nine amazing women of eye and heart. They’re all included at the back of the book. They helped me get to the longlist. Eye Mama can only include women who are empowered enough to take a self portrait and who have a camera. Developing countries, Muslim countries for instance, are going to struggle more with getting those images out on social media. We have loads from South America, and we're getting more from Asia. As the platform grows, so does the diversity and inclusion. I'm really proud of getting to places like Malaysia, Indonesia and India, which was not easy to get to as a platform with no funding, no team, and only a social media hub. This meant the open call was crucial. We did that on Picter. It was funded by MPB. I knew I had to do that to get from Instagram to the book as you have to get all the images officially signed off and at the correct resolution.

Matt Giving Me and Injection © Rachel Cox

I then got the number of images to 400 through deciding what narrative matters - which countries, what diversity. The flavour of Eye Mama is showing the light and dark of photography, of mama life and of care. It’s a peephole into homes worldwide; what do things look like behind closed doors? We are trying to highlight care and empathy but also to look closely at the details, the imperfections, the beauty, the hardships and all that duality and juxtaposition. The light and dark of photography - you can't have one without the other and motherhood is the same.

I got to know everyone, so probably up to 200 women. They’re like my sisters, and I really wanted to include them. How do you not include them? How do you lose an image about cancer, IVF or divorce? It’s not just an image, it's a story. That is really hard. That's why I also want to make an archive project. The book is the beginning. So, from the seed idea, it took three years to the day to get to the publication of the book.

Of my Body © Sapphire Anderson

When you had that first seed of an idea did you know there was going to be a book?

I knew that a book would be an historical artefact that I could have on the shelf. I would like it to be looked back on in 100, 200, 4000 years, if we survive that long! Then you see all these Eye Mama stories, told by women, as opposed to the historical male gaze that we've had on our shelves. Men went to war; men were photojournalists. It was their stories being told, the same as it is in cinema but that’s slowly changing to a female gaze. We want to tell our own stories, we want it to be from our point of view.

Dad and Daughter © Sophie Harris Taylor

This is not anti-male, we need them to support motherhood and care. This is saying we need to highlight what mamas are doing just like you would any other underdog. That's really crucial in the project. So, when you ask how I curated it, I had to make sure that it was all the unseen stuff. I wanted the visual pleasure to be there so that people would be drawn in. If I'm alienating people, if this is just for mother artists, I'm not doing the work. Motherhood isn't just for mamas, it is for humanity. We're all children to someone. Therefore saying motherhood is for mothers is really silly. It's like saying race is only for people of race or disability is only for the disabled. That is a very backwards way of looking at things. What we have to say is, this will affect us all and we would be a better society if we do look at these things.

Neighbours Tomatoes © Lisa Sorgini

What I'm trying to do in the book is to make sure there is visual pleasure, enough to draw people in; to make people want to look. Then once you've drawn them in, you can tell them any story you want. That's the trick of photography and any visual arts. You want to make sure you draw everyone in so that children and men and non-parents, non-carers, non-women, anyone can just pick up the book and enjoy the mama gaze. That’s the storytelling of great photography and then the undercurrent slowly seeps in. What are we actually looking at? Is this hardship; what's this identity? Then hopefully you get some empathy and connection. Through empathy and connection can we get a shift in the perspective of the whole concept of what care means?

It won't just happen from one book. But if there's one book and then one exhibition, ten articles, fifty podcasts, a hundred TV shows - that shift is slowly going to change. Instead of having one storyteller, you're going to have a hundred storytellers. Fifty of them will be women, and fifty of them will be mamas, and that's a much more diverse, inclusive way of looking at the world. In history, especially in a pandemic or historical times, you want storytellers, and that includes different races, different ethnicity, different sexuality, and different stories from the makeup of life, whether you’re a carer or not.

I see a lot more writing happening about motherhood now. I see more conferences. I see more women publishing books, and photo festivals trying to highlight women and the mama gaze. When all of these things happen together, there will slowly be change. Look at what's happening in the States, and even here, with abortion rights. What’s happening everywhere in the world. There's no equal pay for women, and no free childcare. I'm not going to go into government. But what I can do is highlight other women's work. I felt my calling was to curate this gaze. I had to give myself permission to curate what I love; to make the book I wanted to have - I wanted to see - in the best way that I could at this particular point in time. In ten years’ time, I might make a different book. The book doesn't include everyone. I haven't promised to include every woman who's ever dealt with motherhood, I can't, it's out of my capability. I made it in this gap when my kid was five. I just about had my head above water. I often say you're in a storm or in the forest when you have young kids and you're not going to make a project, you're only going to survive. You might photograph your own reality if you're lucky. But usually you're just going to be in survival mode.

How have you found the wider photographic community and who has been supportive of the project?

I can't say only women were supportive and men weren't or the other way around.

The photographer Rankin was the most brilliant surprise. There's a lot of bad sides to Instagram - the trolling and the censorship. Censorship is horrific for women and mothers. We got loads of images taken down of breastfeeding. We still do and at one point our whole page got taken down. That was heartbreaking after all the work I put in. The book was completely paid for by TeNeues, but they don't pay for anything on the platform. The community exists in free form, which is quite tricky, because TeNeues are just looking at the book, whereas actually, the book is nourished and funnelled through the community. It's been tricky to manage, I'm still figuring it out.

Rankin called me in to be photographed, because he was doing this project called Unseen about censorship on Instagram. That includes lots of unseen communities - trans, non binary, and women empowered platforms that all got censored. I really didn’t want to be photographed by Rankin. I'm too old and too tired. And Rankin to me was the male gaze, what am I going to do there? Actually, it was a misconception; l did what other people do to me. People think I’m just all about “go mamas" and all into nappies, and motherhood. No, I'm into photography, and what motherhood means. I was putting one and one together and decided that Rankin is this, that and the other because this is what I’ve seen in the media; this is how he's perceived, instead of assessing him when I met him.

Anyway, I went to him, and he took a portrait of me, which was great. He really let me do whatever it was I wanted to do. I’m terrible in front of the camera because I'm really self conscious. He did a really great job. First of all, he made me feel good, he saw me, he talked to me and didn't ignore me because I'm a forty something year old woman past her prime for most male gaze opinions. He was very supportive of the Eye Mama project and thought the platform was one of the most impressive he’s seen. He really encouraged me to keep going with it. To hear that from Rankin was really empowering. He saw the power of the work. I think he realises moving forward that he can use his power to empower others. He helps a lot of people get visibility, including Eye Mama. He connected us to TeNeues. He put a good word in, and then I pitched it to them, and they liked it and took it on. I owe him the publication of the book. Sometimes all it takes is a good word from one person with influence to get you in the door.

This has been a rollercoaster. It hasn't happened in a day or an hour. I've had times where I was on the floor crying in disappointment, being disillusioned thinking it's too slow, thinking I have no money and why am I doing this? And then I remember that there are so many grateful mamas.

Eye Mama: Poetic Truths of Home and Motherhood is printed by TeNeues.

Header image: Playing with the Shadows © Paula Brandao

This article was published in WE ARE, The Women in Photography magazine, June 2023.

Join us RPS Women in Photography (£10.00 pa)