A Cévenol garden in 72 micro-seasons By Louise Sayers ARPS

An intimate portrayal of nature, its cycles, and the delicate balance between all of its elements in Southern France – rooted in the principles of an ancient Japanese calendar.

Bush warblers start singing in the mountains

(Ko micro-season, Feb 9 - 13)

Rotten grass becomes fireflies

(Ko micro-season, June 11 - 15)

These lyrical lines are from an ancient seasonal calendar, used in Japan for over a thousand years. First adopted in the sixth century from Chinese sources, this almanac was later rewritten to define minute changes in nature, a more precise version specific to its neighbouring country. In this calendar the year is split into four seasons known as “Shiki” – based on the same seasons we are familiar with today – and then subdivided into 24 “Sekki” points, beginning in early February. The latter are based on the moon’s orbits and other natural phenomena such as the solstice and the vernal equinoxes. Finally, each Sekki is further broken down into three periods, resulting in a total of 72 “Ko” or micro-seasons within each year, lasting around five days each.

When I first came across this traditional calendar I was struck by how an age-old approach could seem so relevant and modern, relaying a sense of ongoing cycles and alive to the ebbs and flows of nature. As our lives become more and more filled with digital sensory overload, slowing down and savouring these tiny transformations in nature seems ever more vital. Similarly, with 2024 being the hottest year on record, noting how small shifts in weather patterns can affect a whole ecosystem seemed like a timely reminder of how climate change can affect the balance of nature. On a more personal level, I wanted to find moments of calm, to be grounded in the present and to fill my year with my own observations of “golden orioles performing” and “high grasses swaying in warm winds.”

"It was the discovery of the Japanese mirco-season that gave me the stucture and sense of purpose that I had been searching for"

Putting down roots in Cévennes

The Cévennes national park lies at the south-east tip of the Massif Central in Southern France, a region known for its resilience and insular wilderness. It is a place of deep valleys studded with tough silver holm oaks, hardy heather and craggy low mountains. No major roads or rail links keep it sparsely populated by humans and with a diverse array of flora and fauna – vast plateaus or “causses” full of wild orchids and butterflies are home to endangered eagles and vultures. Its uncompromising granite outcrops, remote waterfalls, serpentine rushing rivers and hushed chestnut forests harbour histories of subterfuge and secrets.

After a decade living in Kenya and a short period in the UK, I moved to the Cévennes hoping to find a place reminiscent of the open spaces of East Africa, where I could see the horizon and feel connected to nature. The Cévennes has since given me this and more, becoming my home during the past 15 years.

In 2024 I signed up for a photographic group mentoring course with Charlotte Bellamy in which we were encouraged to find a project to follow throughout the year. I knew mine would feature the unique ecosystem of the Cévennes, but it was the discovery of the Japanese micro-seasons that gave me the structure and sense of purpose that I had been searching for. The concept of photographing and captioning the micro-seasons in my Cévenol garden and the surrounding hills was irresistible – a whole year of intense observation and possibility. Furthermore, trying to adapt such a complex framework provided an immediate level of continuity and cohesiveness to the ongoing project, paradoxically giving me the creative freedom to experiment with different photographic techniques.

Sekki season - Winter gives way

The winds from the mountain blow cold but the light has a spring in its step. There is a hesitant haze of leaf and bud across the valley. Change is afoot – the cool air laced with honeyed scent of heather, soft white flowers punctuate the bleak undertones.

There are small stirrings in the garden, a frond unfurls and flexes its newfound energy.

Ko micro-season - Catkins dance in high winds (February 4-8)

Rain turns to sleet and golden catkins dance to the lively tune of the north wind. Winking bioluminescence sparking against leaden skies.

Ko micro-season - Fog fills the valley (February 9-13)

After a night of rain I wake to find I am marooned on a tiny island, surrounded by a sea of feathery whiteness.

A feeling of timelessness descends, of protected isolation with no interruptions, something to be welcomed rather than endured.

Nurturing the process

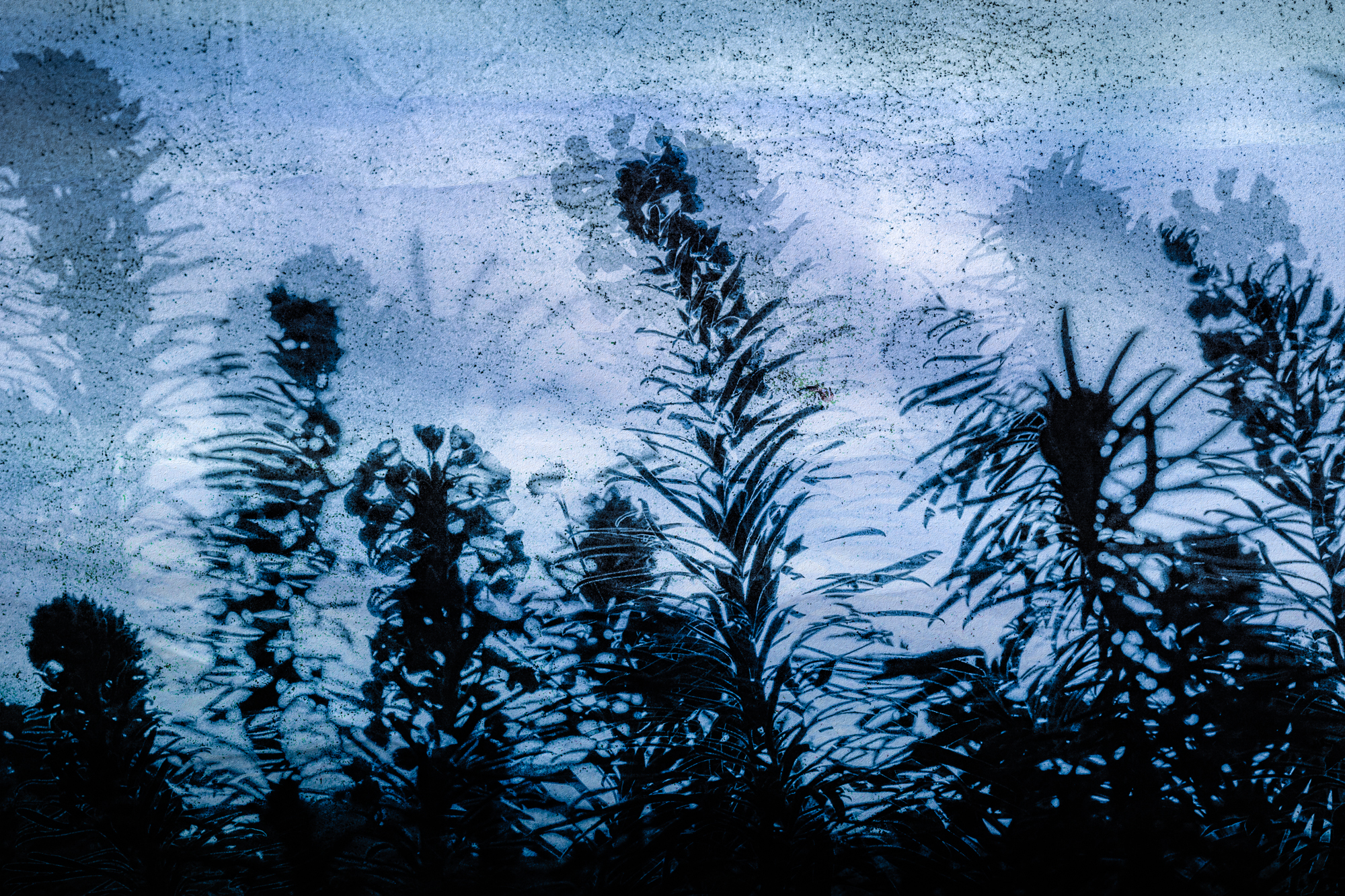

I wanted the 24 Sekki, the foundation of the micro-seasons, to be visually distinct so I chose early on to portray them in black and white. Shooting seasonal change this way creates its own challenges, forcing me to take a more nuanced approach as I am unable to rely on the more obvious changes in seasonal colour. When using my camera in black and white mode I always find it thrilling to look through the viewfinder and see a well-known landscape stripped of colour. Like the bare garden in winter, the eye more readily picks out textures, shapes and structures. The interplay of light and dark, as well as small shifts in tones, are more apparent. Sometimes I use in-camera multiple exposure to realise another dimension – not just a hill’s silhouette, but nature’s various layers including the whisper of a leaf, grass, or even flowers.

For the Ko micro-seasons, I try to find a balance between details and the larger canvas of trees and skies, hills and valleys. Using a macro lens allows me to capture more intimate, calming moments of careful observation – such as new buds appearing, or a curious skew of a withered petal. Other times I use Intentional Camera Movement, or ICM, to mimic the rhythms and sway of grass and flowers. Nothing is static in the garden, and my movement becomes an expression of this fluidity. Responding to the moment or a particular mood using a variety of creative techniques is a freeing, dynamic way of shooting juxtaposed with the rigid framework that I am operating in. It is also a way of keeping the creative spark alive.

Ko micro-season – Hellebores quietly flower (February 14-18)

There are spring gifts to be found. Nestled between rocks and piles of leaves, impervious to cold winds and frosty murmurings, clumps of hellebores are scattered through the garden.

The delicate flowers appear above leathery leaves, in a medley of colours – husky violets and pistachio greens with mauve speckles like bewitched wrens eggs.

Sekki season – Lesser cold

The temperatures flip-flop; today is chilly and overcast but yesterday I watched bees in the sunshine, greedily collecting nectar from the first of the crocus flowers. I try not to be impatient but instead focus on small new beginnings as winter dormancy slowly slides away.

Ko micro-season – A south wind blows off the mountain (February 19-23)

The wind fights back. It toys with the treetops, breaking buds, making new leaves tremble, whistling raucously between the branches.

The weighty flowers of the euphorbia sway manically, caught up in its whirling, swirling eddies like giant corals in chilly ocean blues.

My Cévenol garden

To keep up with the micro-seasons I have adopted an almost daily practice of spending time in my garden. It is a deeply personal place that has slowly grown over the years and melds into the surrounding hills – loved by insects and fungi, wildflowers and weeds. All are welcome. Spending so much time in this familiar space has resulted in my observation skills becoming fine-tuned. When spotting wildlife on safari in Kenya my eye became trained in looking for changes in shapes or shadows. Similarly, I have become sensitive to small shifts in light, like a new spark of white flowering gorse or a slight shimmer of new green shoots.

As a result, my year becomes one of firsts – the first bud on the apricot tree, the first nightingale to sing, the first hellebore, lilac, wisteria flower. The project takes on its own routine and pace, reflecting the rhythms of the micro-seasons. A mindful practice which brings connection to my surroundings and allows me to focus on the present, providing a deep sense of fulfilment.

That is not to say that embarking on a long-term project has been without its challenges. Some days expectation weighs heavy and the familiarity with my surroundings can dull my creativity. However, I have learnt that there are ways of keeping my project fresh. When I feel less inspired I allow myself time to sit in the garden or on the hill, with no expectation of taking a photograph. Invariably there will be something that catches my eye – a “gendarme” sun seeker insect feeding on a hollyhock, the Ampelodesmos grass catching the breeze – and before I know it the familiar itch to capture that moment takes hold. Even on days when the fog closes in, both figuratively and literally, getting outside clears the mind and allows space for a new perspective, a change of view.

The practical aspect of following a project so close to home is a huge advantage and should not be underestimated. Being able to wander in the garden at any time – early morning often finds me in a coat over pyjamas – means I have more opportunity to capture fleeting shifts in light, or the moment a storm comes rolling in. Not having to get in a car is a great motivator for venturing outside and being camera-ready.

Ko micro-season – Forest awakenings (February 24-28)

Remnants of mist hang in the forest, the silence is palpable. Above the treetops the sun appears from behind the clouds. Shafts of light break through the gloom.

A thrush bird, somewhere high up, sensing the change, sings away the last of the darkness. A deep, meditative breath slowly dissipates along with the shadows between the trees.

The seasons ahead

Finding a community of like-minded and supportive photographers has also been hugely beneficial, and having a degree of accountability and deadlines is something I really respond to. Additionally, learning about other approaches to workflow and gaining insight into fellow photographers’ creative and diverse projects is hugely inspiring. In 2025 I continue my project but have also enrolled in a number of photographic courses to expand my learning and hone techniques.

Last year I joined the Royal Photographic Society and I am now working towards ARPS qualification centred on my Sekki set of black and white photographs. Continued experimentation in technique behind the camera, as well as in post-processing and developing my own creative expression and confidence in my photography, are all key to reaching my end goal of completing the project and illustrating all 72 micro-seasons.

Ultimately, observing, noting, tracking and photographing the continuous changes in my Cévenol garden has made me even more curious about this wonderful, complex and diverse ecosystem. The more I observe and discover its metamorphoses and symbiotic elements, the more questions I have. Where do the carpenter bees go after feeding on the wisteria flowers? What is the name of the butterfly with transparent wings that I see on my walks? Am I tracking the dragonfly or is it tracking me? Suddenly 72 micro-seasons feel restrictive. What happens next year if it becomes hotter and drier than ever before? Perhaps plotting the micro-seasons will become a lifelong project. After all, nature adapts and continues, an ongoing harmony of cycles and biorhythms, seemingly without end and which, especially in darker moments, I am endlessly grateful for.

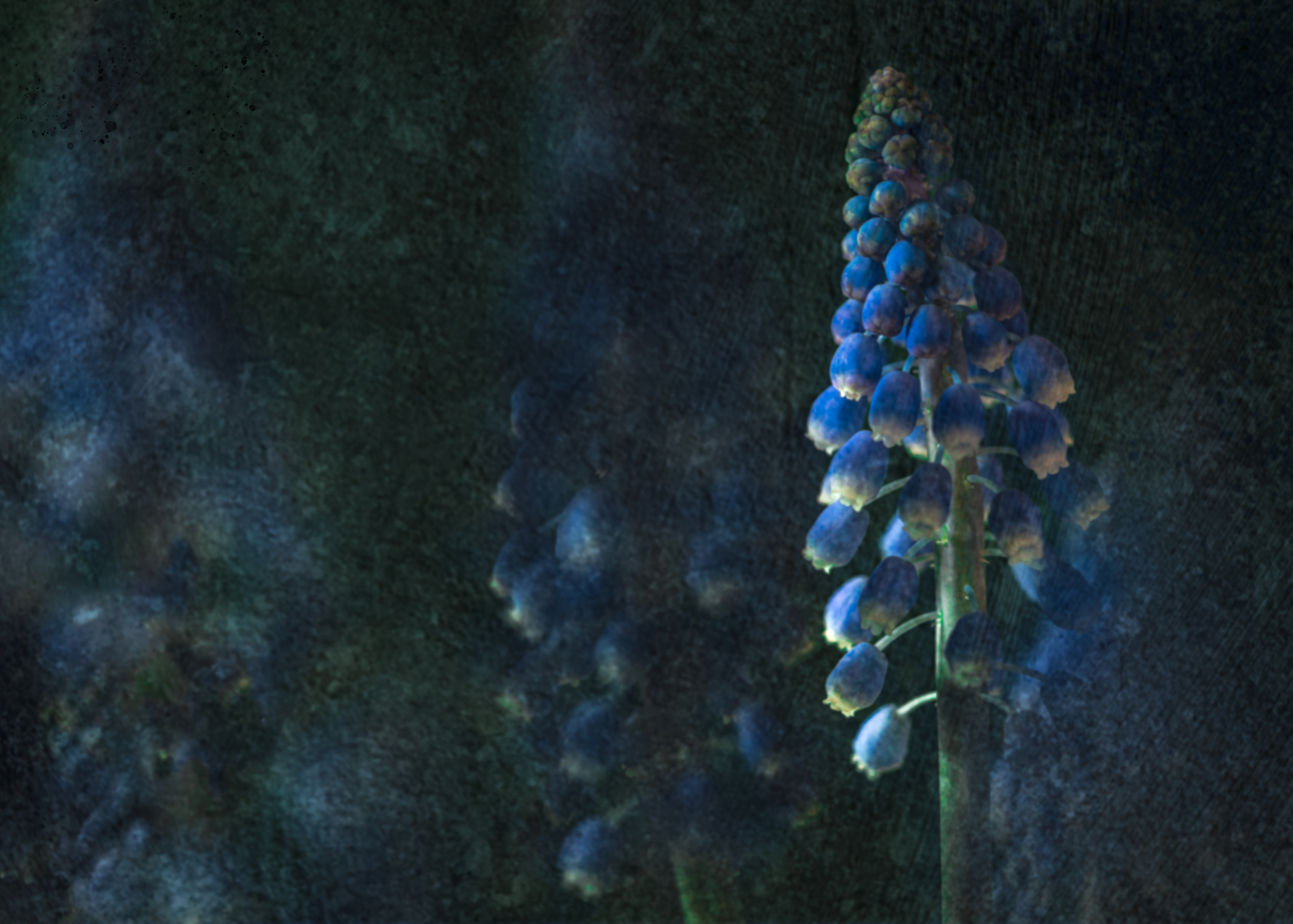

Ko micro-season – First Muscari emerge (March 1-5)

From the cold, stony earth, gifts of miniature flowers are offered. Clusters of bell-shaped petals, bright cerulean blue, edged with white scalloped petticoats. Their small stature belies their resilience, staying underground to survive the winter wet and frosts, until the sun draws them upwards.

Soul-lifting blues banishing the winter doldrums.

All images © Louise Sayer ARPS

About Louise Sayers

After completing a degree in education at Brunel University, Louise was able to realise her lifelong dream of travelling by accepting a teaching post in Kenya’s Rift Valley. It was there she later found a change in career, becoming one of the first female guides to qualify with Kenya’s Professional Safari Guides Association (KPSGA). After leaving Africa, and a brief return to the UK, Louise moved to the Cévennes in Southern France – its rugged landscapes and remoteness fulfilling her desire to once again be immersed in nature.

Photography and writing have always been Louise’s creative outlet, her camera a trusted companion throughout her travels. Continually curious and inspired by nature, she strives to explore and learn more about the landscapes, flora, and fauna she photographs. Louise also enjoys still life photography and uses seasonal botanicals to expand her creative approach and portray the poetry and drama she experiences in nature.

https://www.instagram.com/fig_tart/