My father and me by Ruth Toda-Nation

Through documenting her ageing father, John, as a way of navigating the challenges of being his caregiver, Ruth Toda-Nation reflects on how the photographic collaboration and process transformed their relationship, helping her to contemplate childhood experiences and, ultimately, heal her inner child.

“My name’s John and I’m a man of peace.”

As a photographer, I like to get to the heart of things and tell people’s stories. Photography helps me understand humanity and delve deeper into myself to understand and explore my unresolved feelings.

John and Me is an ongoing body of work I began seven years ago in response to the challenges of being a carer and a daughter. Through this work, I share my inner dialogue as I explore the father-daughter relationship and capture the pathos of one of the most fundamental human bonds. It is a relationship many long for, but for some, and for me, it has been a lifelong journey full of emotional contradictions.

The work is as much universal, as it is personal. With unpaid carers providing more hours of care than ever before and their value, according to Carers UK, standing at a staggering £184.3 billion a year — the value of care equivalent to a second NHS — it is vital to share our experiences and have conversations about these issues that many of us face, particularly women.

During Covid-19, I put this work on hold to focus on photographing and interviewing Dad’s wider retirement community. This resulted in two projects: Love is a Life Story, exhibited in early 2025 at the RPS Gallery in Bristol; and Our Lockdown Garden, which became a self-published book. This series is about reconciling with the past, navigating the present and preparing for the future. With my father turning 95, we are poignantly aware that he stands daily on the precipice of his mortality.

The past

My parents went to Japan in the 1950s as Christian missionaries — my mother from Australia, and my father from the UK aboard the Willem Ruys liner, a journey of six to seven weeks. They met during mandatory Japanese language training in Singapore, where they fell in love. At the time, strict mission rules governed their lives, including chaperoned dates and a two-year minimum engagement period. They married in Japan in 1959, beginning a 20-year life there, during which they had three daughters, including me.

My father’s life began tragically with the death of his mother Joan, a few weeks after he was born. I came to realise through this project what a profound effect this has had on him. He admitted that he had grown up feeling guilty that he had somehow caused her death. The unconditional love he lost and sought, he eventually found in the message of Jesus. I was beginning to see the picture.

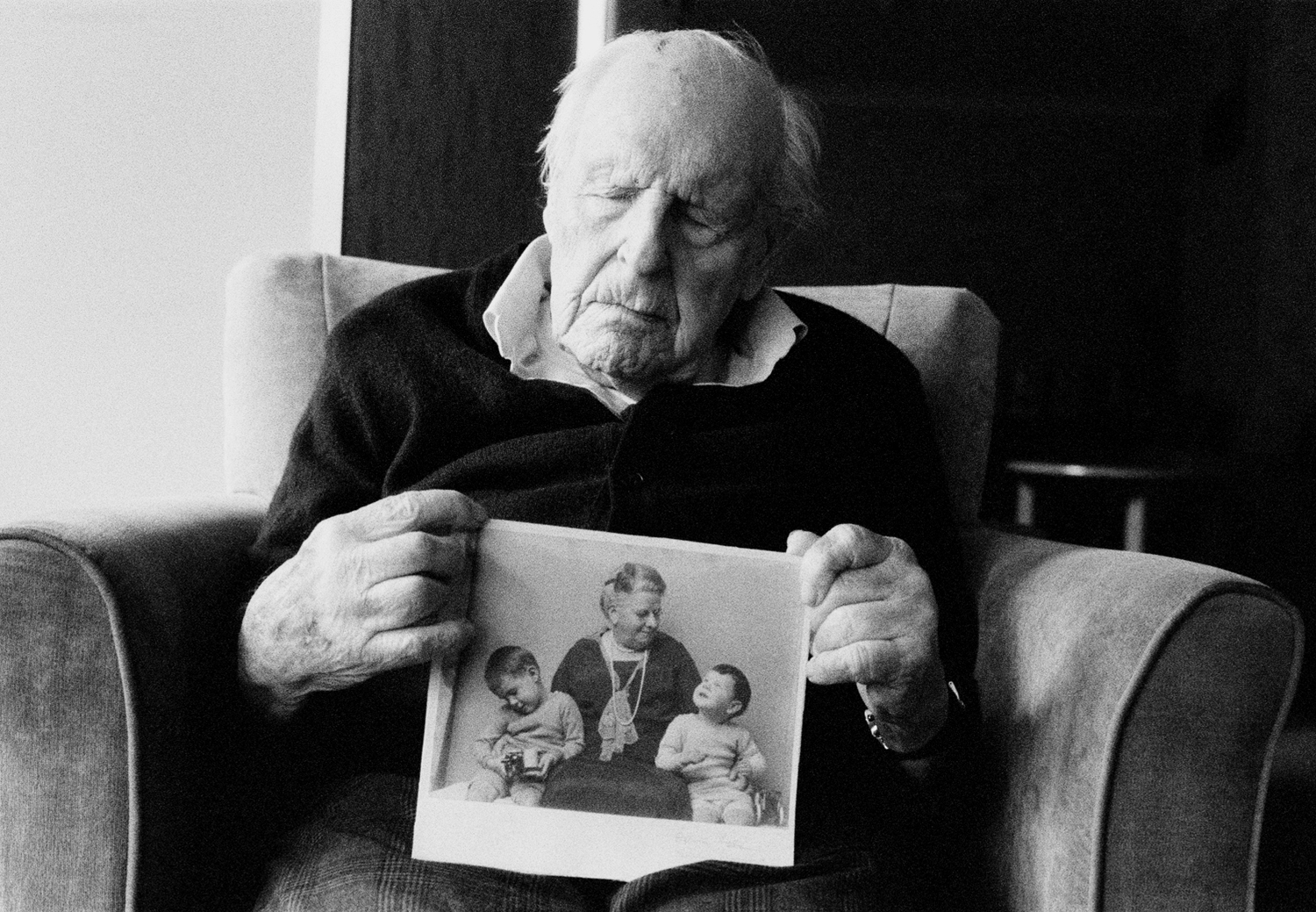

Within our extensive family archive, I found images he took of me as a child in Japan; beautiful, intricate hand-drawn maps of imaginary worlds; every sermon he had ever preached spanning his working career; and poetry he had written from his boarding school days up until the day my mother died 26 years ago. He never wrote again after that.

I needed to care for a father who I loved but had been separated from when I was sent to boarding school at the tender age of six. Caring requires giving and sacrificing, but I felt that my parents had chosen to sacrifice our relationship in their conviction to guide people to Christ. My life had been a series of goodbyes and transience, and of not knowing where I belonged. I had a family, but we had never lived together for extended periods of time.

If I’m brutally honest, I was a reluctant carer. I had put my photographic career on hold to be a parent and aspired to reignite it. I had my business to run. Compounding this, I was aware that caring for a parent regurgitates everything we could never quite resolve. It requires us to confront our inner child and mine was screaming “No!”

The present

I initially called this project No Room for Rumination because my father was consumed by anxiety, endlessly dwelling on the consequences of his past decisions — it was painful to witness. When I started the project seven years ago, his state of mind was very different; he was incredibly needy. To cope, I turn the pain into something meaningful by documenting him and writing about the process in the form of a journal that I upload to Instagram hoping one day to bring it together as a book.

The first images I attempted, digitally and in colour, were of Dad in his dog collar with the Bible placed firmly between us on the table. The distance between us was tangible. I realised I needed a softer approach to draw us closer together and capture those shared, fleeting moments of intimacy. So, I turned back to film and my small 35 mm cameras.

I discovered a duality in caregiving — it became something for me as much as for Dad. This shift helped me feel less resentful and more appreciative of its impact on my life. I turned caring into an opportunity to reconnect with my photographic practice, engage with Dad, learn about his life, and reflect on our relationship. Using my camera, I document our trips to the cafe, the Turkish barber, the day centre, the church, the hospital, and the dentist. I’ve lost count of the times I’ve called an ambulance to his flat, but through it all, my camera helps me detach, process, and cope.

There is also a deeper message to me as a child, almost as if I can reach back in time and speak to five-year-old Ruth, a kind of hypnotherapy. I now photograph him as he photographed me in Japan. I write to heal. We read his poetry and visit his mother’s grave. We share plenty of soft landings and sweet moments that calm my soul and reassure my inner child.

I’ve realised that this project is not about “goodbye”, though it is in the physical sense. Instead, it is a series of “hellos” and of getting to know my father in a new way. Moments of bonding, forgiveness and, ultimately, acceptance. There’s a Japanese word for this: “OyaKoko” (親孝行). This is a concept that teaches both parent and child to cherish this special time together, ensuring no regrets remain when it’s finally time to say goodbye.

Embedded in the work is a narrative that speaks to larger universal truths about caring for an ageing parent. Research shows that what carers want more than anything is to be seen, acknowledged, and empathised with. There is a desperate need for policymakers to act and provide support to unpaid carers as well as invest financially in a social care system in crisis.

The future

I have noticed that carers sharing upsets people. Talking about death equally so. People don’t want to know the hard reality. In response, I am determined to immortalise my father, to tell the story of his existence to a world that shuns frailty and death and turns a blind eye. A frailty that will eventually come to most of us. I do it because I admire his strength.

The more time I’ve spent with my father as an adult, the more comfortable we have both become in revealing our vulnerabilities and consequently our relationship has become stronger. Dad recently said, “I have no regrets. I am ready to go.” He seems to have entered a kind of nirvana, a sort of freedom from matter; his anxiety has gone. Despite everything, he has never lost his faith. He is still a man of peace.

I look at him and he is frail. But I’m less bothered by this and the fact that he’s fading because these photos show more than this. I am less fearful of the future because he is at peace now and so am I. I have come to a place of acceptance and reconciliation and so has he. I look at this handsome man and know that I am who I am because we share a unique history and this strange but loving bond of parent and progeny.

All images © Ruth Toda-Nation

About Ruth Toda-Nation

Ruth Toda-Nation’s photographic practice is informed by a nomadic childhood bridging two cultures, Japan and Britain. She began her photographic journey in Liverpool in the 1980s and later worked in rural, northern Japan. Her intimate approach flows from a deep emotional connection with the people she photographs, and interweaves themes of family dynamics and community bonds while reflecting on ageing, transience, and departure.

A fluent Japanese speaker, Ruth works as an interpreter, mediator and educator. She brings a unique perspective to her photography combining images with words drawn from interviews and conversations to give voice to people and communities. She is driven by a desire to understand more of humanity and herself to effect positive change. She holds a degree in Photography and Film from the University of Westminster.

Love is a Life Story was a winner in the RPS Documentary Photography Award (2023) and her book Our Lockdown Garden is published by The Mindful Editions (2022).

Instagram: @ruthtodanation