The Garden of Maggie Victoria Combining old family photos with new work to revive the story of a long-forgotten great-grandmother and her ordinary, extraordinary life.

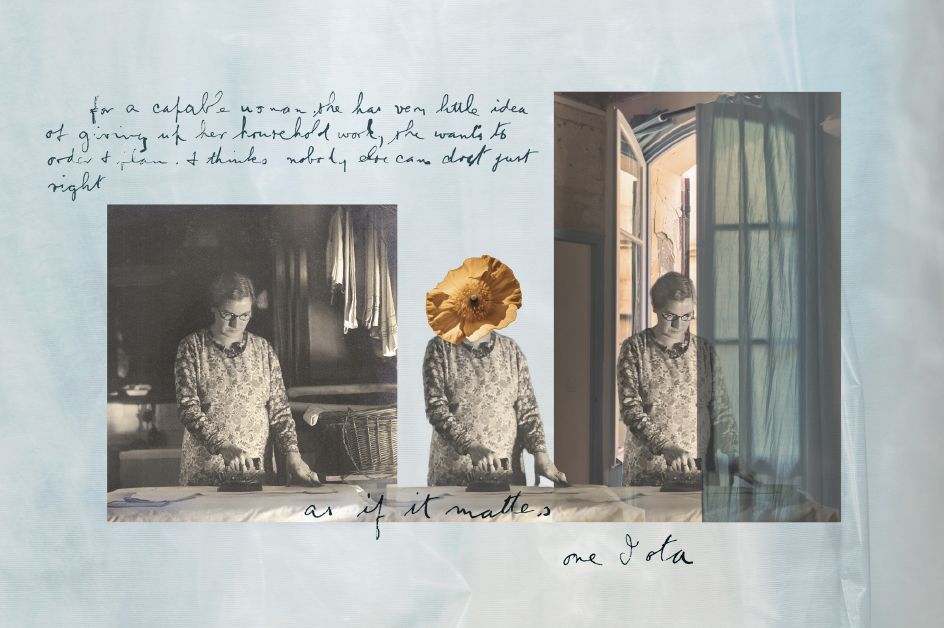

It started with three scanned old photos. One was a formal engagement picture. In another, a young mother played with two small children. In the third, an older woman was doing the ironing.

My mother had emailed these scans to me from the UK when I began to focus full-time on photography. These analogue images were part of a chaotic trove of family photos made over decades by Frank Sellers, my great-grandfather and a keen amateur photographer in Chorley, Lancashire.

The scans languished in my inbox for four years until a quiet pandemic day in January 2022. The woman in the pictures was my great-grandmother, Maggie Victoria Sellers. Other than that, I knew nothing about her. In contrast, myths and legends abounded about her husband Frank, who lived to a ripe old age.

Maggie Victoria died after a fast-moving illness in May 1943. She was just 56. Frank remarried within the year, and no one spoke about her after that, not even her three children.

This explained why my relatives and I knew little about Maggie Victoria. I was shocked that someone could inadvertently be erased from our family history, yet without her, I would not be here. I felt a strange kind of grief for someone I had never met.

Two years on, I have created a series to revive my great-grandmother’s story and honour her legacy. The Garden of Maggie Victoria integrates archive images, documents and letters with my own nature-oriented photos made in Vancouver, Canada, where I now live.

The process of creating and exhibiting these works has been challenging and interesting in more ways than I could have imagined. One of the most satisfying outcomes is the conversations it has sparked with strangers. Many families harbour mysterious ancestors, and bringing Maggie Victoria’s story to life has been a catalyst for others to share their experiences with me. They have a wealth of questions about the people in their own families who have disappeared, or who had undeserved reputations, who never talk about their early life, or, indeed, who died unexpectedly.

The archives revealed a wealth of photos to sort through © Rachel Nixon

Piecing together a life

It took some time to learn more about Maggie Victoria. Nobody who had known her was still alive. Two of her grandchildren – my mother Anne and my uncle Tony – turned out to have piles of photos and documents bequeathed by my great-aunt Gladys, Maggie Victoria’s eldest child. Thus began a months-long process of Anne and Tony sorting through the piles. We all tried to work out when the images featuring Maggie Victoria were made, and what they told us. There were more photos than I could have hoped for, but few details beyond the birth-marriage-death bureaucracy. They tried to fill in the gaps with piecemeal information dredged up from decades-old memories of what little their parents and others had shared.

I created a timeline to make sense of the material and determine important moments in her life. There were no images of Maggie Victoria before her 18th birthday – not particularly surprising for someone born in 1887 to a poor family in Liverpool. A tailoress by profession, she was first engaged to “WF” – so says an engagement ring that she bequeathed. We can sadly assume the worst for WF in the conflict-ridden early 20th century.

In 1915, she became engaged to Frank Sellers, a widower who spent his life working in, and then owning, a cotton mill in Lancashire. Short in stature, Frank had a larger-than-life personality. He was a champion gymnast and locally renowned for saving people from drowning. There were no photos of their wartime wedding that October. The couple set up home in Chorley, where they had three children – two girls and a boy. There were plenty of images of Maggie Victoria as a young wife and mother in the 1920s and early 30s. The photos dwindled as she aged, with children more prominently featured. Later, a significantly older looking woman is pictured, working in her beloved garden, or doing the housework. Ill health came for Maggie Victoria in her fifties. A spell in hospital in 1941 prompted her to write her will. Then, in the midst of a stormy spring in 1943, the end quickly arrived.

The last letters

It was hard to get to know Maggie Victoria through the photos and documents. Inspiration and a tragic realization came in a set of eight undated letters to her eldest daughter Gladys, who had begun working and living away from home.

Reading them casually, and out of order, offers a picture of household goings-on amidst World War II, while Maggie Victoria is battling health niggles. I looked for clues to put dates to the letters and put them in order. The clues are too numerous to detail. However, Maggie Victoria routinely transcribed listings for the radio programmes she thought Gladys would be interested in – days of the week only, no dates or months. Using the BBC’s impressive online archives, I was able to find corresponding programme listings for the exact date and put the letters in order.

That’s when the realization hit.

Reading the letters in order, Maggie Victoria becomes progressively weaker. She is reluctant to give up household work until she is forced to stay in bed, even though it is “most annoying”. Her heart is “wobbly”. She has fluid on the lungs. The doctor gives her antibiotics that make her violently nauseous and avoids giving a prognosis on his increasingly ailing patient.

The last letter, on 16th May 1943, is written to Gladys by husband Frank and younger daughter Doris (my grandmother), with amplified concern for Maggie Victoria’s health. Still, Doris says there is no need for Gladys to come home. Maggie Victoria died the next day, 17th May 1943.

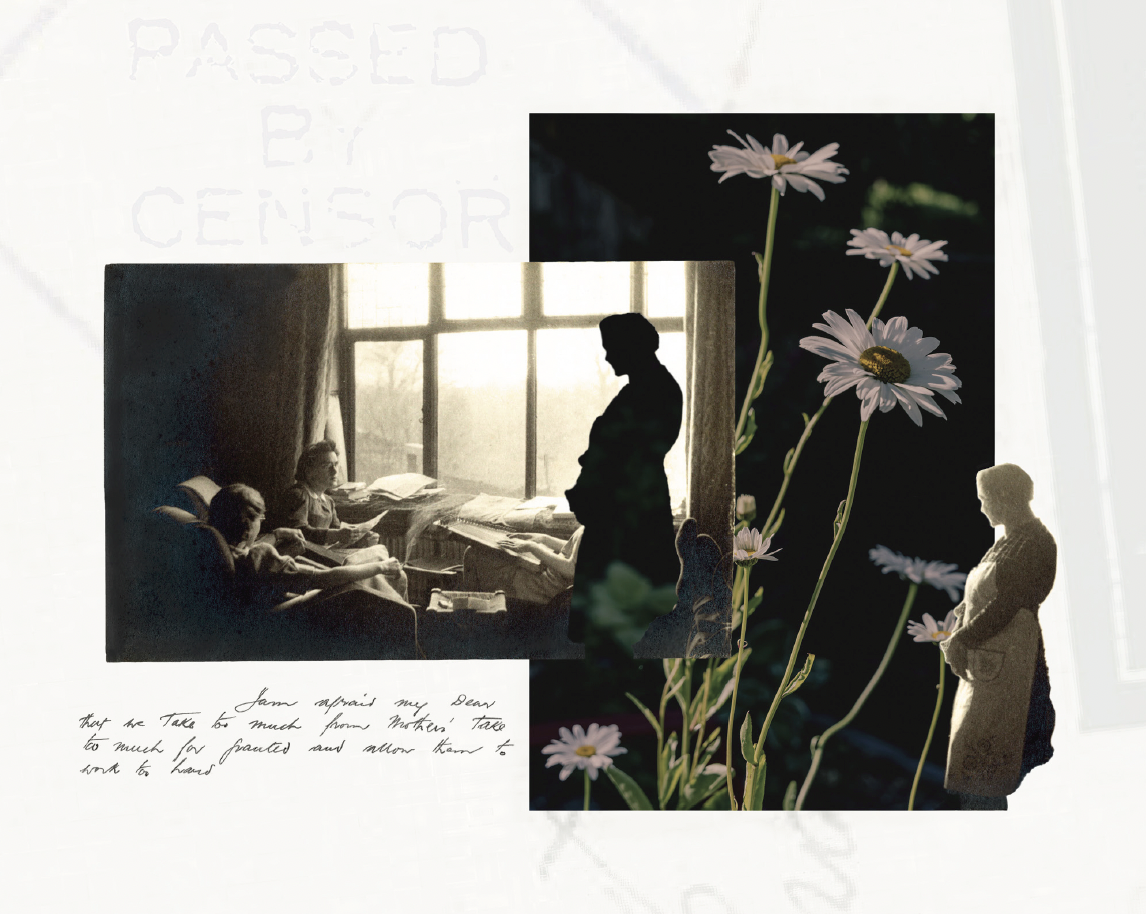

Gladys did not get to see her mother before she died. This is why the letters matter. They are her mother’s last contact with her daughter before her demise. Knowing what is coming, it is hard to read the letters in order. They give an insight into the last weeks of a woman dedicated to her family and determined to put on a brave face.

Around her, everyone is doing the best they can during wartime.

‘We take too much from mothers’

Knowing the speed and shock of Maggie Victoria’s decline made me more determined to make the series. As a fellow photographer, and not wanting to erase her a second time, I thought it important to keep Frank’s original images largely intact. I decided upon college as a means of putting myself in the work. I integrated nature-based images to connect with Maggie Victoria’s prowess as a gardener and to reflect the natural world that surrounds me in western Canada. Where available, I included objects she had left, such as a tablecloth embroidered with the names of her friends and family, and a christening dress.

New Life © Rachel Nixon

While I used digital colour images alongside the analogue monochrome images, I worked to ensure that the colour complemented the monochrome rather than jarring with it. I wanted to make coherent collages rather than noisy contrasts.

Fondest Love From Mother. This was how Maggie Victoria signed her letters © Rachel Nixon

From the letters I extracted phrases that may have once seemed inconsequential but now point to important truths. Chief among them was an extract from a letter to my grandmother by Maggie Victoria’s brother Lionel who had emigrated to Australia. On learning of her early death, he wrote: “I am afraid my Dear that we take too much from mothers, take too much for granted and allow them to work too hard.”

For me, this sentiment summed up a life of selflessness, overwork, and lack of recognition. Was it the whole story, though?

Changing Tides © Rachel Nixon

A Capable Woman © Rachel Nixon

I was sometimes annoyed on Maggie Victoria’s behalf about her visual portrayal as a mother, housekeeper, and dutiful wife. There were very few images of her enjoying herself, or being free to do what she wanted. This seemed to be her life, and how Frank saw her. At the same time, I had to hold my 21st century opinions in check. As my mother commented, this was a “morally upright, temperance household in Lancashire in the 1920s”. Domestic chores, she noted, “were a respectable thing for a married woman to be doing – and what was expected of her.”

It has been interesting to observe the variation in papers on which Frank used to print in his self-built darkroom. Even on images made the same day, the paper changes, as seen in the two photos in my piece Changing Tides. Elsewhere in the archive, Maggie Victoria is pictured skinning a rabbit, in more of a Polaroid format. It seemed hard for Frank to get hold of photo paper – especially in wartime. On 12th May 1943, he wrote: “Perhaps… I shall turn again to the old hobby provided material can be got.”

Whose truth?

The question of “truth” troubled me. As a former journalist, I was painfully aware of the gaps in Maggie Victoria’s story and the lack of any first-hand witnesses who could confirm or deny my account. I had to satisfy myself that the gaps were a part of the story and that my role was to bring the essence of Maggie Victoria to the fore.

Was this even my story to tell? If I were to talk with Maggie Victoria today, what would she think about this project? Would she have allowed me to move forward with it? Would she have been embarrassed by the fuss? Or would she be proud that one of her descendants was carrying on her legacy as well as the family photographic tradition? It’s something I wonder when I observe others’ projects made with archive material, sometimes involving relatives, other times using found images of strangers. What right do we have to intervene in their stories? Does “art” make it alright?

“We Take Too Much From Mothers” © Rachel Nixon

My photo series is nearing completion. More people know Maggie Victoria and her ordinary, extraordinary life. It doesn’t feel quite finished, and I would like to create a book, adding artefacts, stories and more of my own images along with the full letters.

We can learn so much from our own ordinary histories. Better understanding our origins and those of the people related to us can help us understand ourselves. That’s one of the many lessons my great-grandmother Maggie Victoria has taught me.

About Rachel Nixon

Rachel Nixon is a British-Canadian fine art photographer – and former journalist – based in Vancouver.

Having lived and worked across continents and cultures, Rachel explores issues such as a desire for connection with one’s heritage, and the wider world, as well as secrecy, and memory.

In 2019, Rachel graduated with honours from the VanArts photography program. Her work is exhibited internationally and has received accolades, including four Julia Margaret Cameron Awards. In 2023, her series The Garden of Maggie Victoria was selected for the Pacific Northwest Drawers, and designated a finalist in Critical Mass and the Royal Photographic Society’s IPE 165.

Checking the finished prints for exhibition © Alfred Hermida

Before committing full-time to visual art, Rachel had a 20-year career as a journalist in the UK, US and Canada for the BBC, CBC and Microsoft where she developed and ran digital news services.

Rachel holds a first-class degree from the University of Oxford in Modern Languages and Literature, and is fluent in French and German. Her international experience offers a unique perspective on identity, place and belonging, and connections we share despite polarized times.

This article was published in WE ARE, The Women in Photography magazine, March 2024